Much of the Educause Leadership Institute talk today was devoted to change. The institute faculty referenced three kinds of change: developmental, transitional, and transformational. I think these are roughly the same as Holman’s three types of change that I’ve discussed before: steady state, incremental, and emergence. I’m thinking the three types of change tall, grande, and vente (hey, I’m from Seattle!). Clearly, we are focused on the third category–the most disruptive. Why else would we have flown all the way to Chicago in the middle of summer?

During the learning technologies discussion, the faculty gave us a fascinating scenario (I’ll paraphrase):

It’s the year 2018 and you are the CIO. You’ve been CIO for five years. Now, after five years in office, your university has been written up in the mainstream press for being one of the most innovative universities using technology in teaching, learning, and research. As CIO, what was your role in bringing this about? What are two specific contributions you made? Was this the change tall, grande, or vente? I think everyone in IT should do this exercise periodically.

Two perspectives on technology and disruption

A couple of great articles. I recommend reading both, back-to-back.

“How Disruptive is Information Technology Really?” by Judith A. Ramaley from the Educause Review.

“The Innovative University: Changing the DNA of Higher Education” [PDF] by Henry J. Eyring and Clayton M. Christensen, from the American Council on Education.

I’d love to hear what others get out of these two very good articles. I challenge you to think about the three types of change framework as you read both. I interpret Ramaley as arguing that, while significant, the digital age brings transitional (incremental, grande) level change. She writes, “The new technologies give us much more to work with and a better way to explore topics in depth, but we still need to do so in the company of others.” Ramaley certainly points to the serious changes demanded by new technology capabilities. She fully recognizes that instant access to the world’s knowledge, online connectivity, and other marvels will force universities to evolve. But I get the sense that her position predicts more gradual, evolutionary change.

In Holman’s model, I think she used the example of change to a national government. In that example, passing a new law is steady state change. Amending the constitution is incremental. Chucking the constitution to go with a wholly different political system all at once is emergence. Holman sets a pretty high bar for what it means to claim the grand prize at the change-a-thon. It doesn’t mean maybe sorta kinda over time and nobody’s feelings get hurt.

So, I see the sense of Ramaley’s case. Yeah, tech matters. It’ll really alter the constitution of higher ed. Over time, it might not look anything like it used to. But we won’t be tearing down colleges, ending promotion and tenure, or getting rid of credit-hours any time soon.

Eyring and Christensen are a bit harder to pin down, but I think they are arguing that we are facing emergent, transformational forces. They go further, using the whole DNA concept as a metaphor. That is to say, the current species of Academia was shaped by a set of very specific adaptations suited to a particular environment. And that environment just went bye-bye.

As with a species, they are doubtful that most of Academia can adapt quickly enough to survive, and that new species will take over. Like when the asteroid/climate change/alien attack or whatever changed the planet so that the dinosaurs couldn’t survive, the mammals took over. A few dinos managed to turn into birds and gators, but their time was over. By the way, the article doesn’t talk about evolution the whole time, that’s just me. Eyring and Christensen spend most of their time talking about the history of Harvard to show the specific conditions to which higher ed adapted and why. This helps us see that practices such as tenure, majors, athletics, and credit hours aren’t immutable laws of physics–but rather artifacts of specific environmental pressures.

Is change just happening to us? Or are we changing stuff?

Coming back to our conference–and the question our table faced about what sort of change we’d bring as CIOs in 2018–we quickly realized that it’s not a prediction, like wondering if it’ll rain tomorrow. We aren’t asking, huh, what’ll this change do to us?

It’s a decision. A bunch of decisions, made by a bunch of people. Like us, our students, voters, faculty, etc. How much change are we willing to bring about? What’ll we put on the line as leaders to make sure our we’re really giving students and our communities the best possible expression of our values?

[Quick personal soapbox: notice I said “our values” and not “market values”. I don’t think the mission of education is workforce training. Jobs are boring. I don’t want a job, I want a passion that somebody is silly enough to pay me for. I think education is about building civil society, giving everyone a chance to achieve their dreams, equalizing opportunity, and ultimately, giving back. If Google gets better hires along the way, bully for them. Google, by the way, also has a mission statement that says nothing about making money or selling ads. So there.]

Because of all this, I had an insight about myself. Back at the ranch, I’m in charge of brining IT Service Management (ITIL v3) to our IT department. Our project has finished the research and is getting ready to broadly engage our IT group about what ITSM means for them. I asked our Leadership team a question last week. I asked something like: “When I start rolling out ITSM, how crazy should I get? On the richter scale, do you want a 2, or a 7?” I felt really inarticulate and I don’t think I made myself understood. Now, I realize what I was really asking. ITSM is one of the many practices that can totally re-make everything about IT, or can just be used to tweak a few things. I was really asking them what type of change they could handle: tall, grande, or vente?

I wish I’d put all this together in my head a week ago!

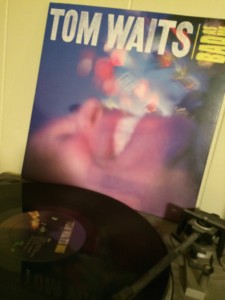

Tom Waits from a long time ago. His voice doesn’t sound like a thousand cigarettes in a meat-grinder yet. It’s that kind of evening.

Tom Waits from a long time ago. His voice doesn’t sound like a thousand cigarettes in a meat-grinder yet. It’s that kind of evening.